The Easiest Moment in Human History to Plan a Party

Do you remember Facebook Graph Search?

In 2013, Facebook announced a new feature that it touted as a bold and revolutionary new way to search the web. It was called Graph Search, and it would index a powerful dataset that Google could never access: your social graph. By taking advantage of Facebook’s incomparable knowledge of who you are and who you know, Graph Search could help you search not just the web, but also your own life. It launched with a handful of classic Web 2.0 promises like “when you’re in a new city, you can search up which restaurants your friends liked.”

Graph Search is dead now—essentially killed in 2019—and so are social networks.

What we have instead is “social media,” a term often used interchangeably with “social network,” but different in critical ways.

As a society, we haven’t really reckoned with the death of social networks—the names of the platforms haven’t changed and our networks still live there, so why would we?

But the way we use Facebook, Instagram, and the rest has changed drastically, and the way we feel about them has changed even more.

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg memorably embarrassed Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT), and by extension the first serious attempt to regulate Big Tech, when he smirked “Senator, we run ads,” in response to a confused line of questioning about what exactly Facebook’s business model was. That moment is so famous—and indisputably correct—that it’s easy to forget Zuckerberg originally had a very different idea of what Facebook was for. In 2007, Facebook declared in a press release its intention to become an open platform for social applications:

Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg today unveiled Facebook Platform, calling on all developers to build the next-generation of applications with deep integration into Facebook, distribution across its “social graph” and an opportunity to build new businesses. “Until now, social networks have been closed platforms. Today, we’re going to end that,” Zuckerberg told an audience of more than 750 developers and partners. “With this evolution of Facebook Platform, any developer worldwide can build full social applications on top of the social graph, inside of Facebook.”

It was a remarkably coherent vision for a social network. Facebook would own your social graph and let other companies build experiences based off of Facebook’s knowledge of who you know, where you live, and what you do. In this world, Facebook’s business would be to cultivate that graph so that it was maximally accurate about what your social connections were, and thus maximally profitable to sell access to. And crucially, Facebook used to have a product that incentivized its users to maintain an accurate list of who they knew in real life.

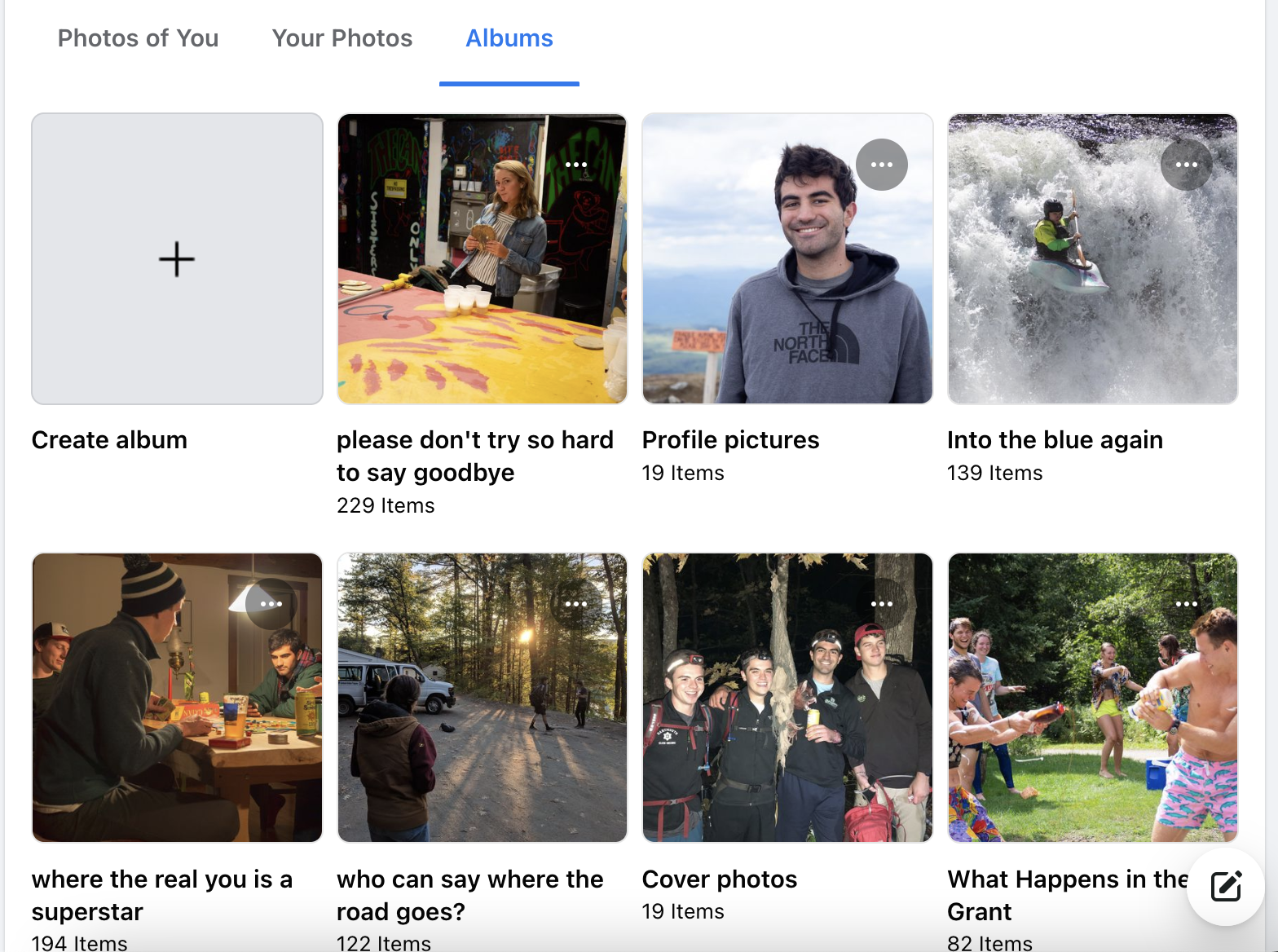

The easiest moment in all of human history to plan a party was the five-to-ten years when everyone you knew regularly checked Facebook. You set an event time and location, then invited people by just searching their names. You could plan a big party that would appear on people’s newsfeeds, or a small party visible only to a select group. It was incredibly easy to keep everyone on the same page because the hard part was already handled—everyone was on Facebook.

The core features of early Facebook were designed to augment some social activity that took place in real life.

Photo albums publicly documented something you had done, groups made it easier for clubs or schools or communities to share information, events helped you gather, and so on.

This was not just the best era to be on Facebook, it was the best era for social networking, because Facebook during those years was the only good social network that has ever existed.

But being a social network is not a good business.

It turns out that there is precisely one great business model if you want to host user-generated content, for free, at venture capital-approved scale: You run ads (Senator). And if you want to make money selling ads, then you do not care one whit who people know, you care what people like. The more accurately you can figure out what your users like, the more valuable the advertisements that you place in front of them become. And that is the business of social media, not social networks.

Social media is a goddamned nightmare. Its reason for existing is to conflate the social connections I want to maintain with the entertainment I want to consume. Your social graph is only useful insofar as it can be weaponized to make you horrifically afraid that some essential component of your actual human relationships will be lost if you ever close the app. So you stay in the app, teaching the app how to sell you more valuable ads while simultaneously consuming the ads that you helped make more valuable.

This past summer, when Meta generated an enormous backlash by briefly making the Instagram feed (even) more like TikTok, Instagram head Adam Mosseri went on a press tour saying that he’ll roll back the changes for now, but also, users are all lying to themselves about what they really want. “People are interacting more with video relative to photos more and more over time,” Mosseri explained in an interview with Platformer. “That’s been true since long before we started leaning into recommendations in feed.”

Yes Adam, you absolute jabroni, people engage more with videos—because videos are more engaging. That’s why Ken Burns pans across old photographs set to sad violin music. The implicit assumption that we’re all supposed to accept is that it is Instagram’s core mission to keep you entertained and that it is not only logical but inevitable that Instagram will pivot to the thing you spend more time doing. There is simply nothing social about that mission; social is the bait, media is the trap.

“Alex, you’re being unfair—of course Instagram wants you to spend more time in the app, that’s how they make money.” Precisely. Many of the other applications on my phone do not work this way. The Uber app would like me to use it to hail a car, but there are only so many rides I could possibly need—it is not engaged in an arms race to hold my attention. The Signal app sends messages with an interface that is so quick it’s almost shooing me away. And an application whose primary function is as a social network can keep me connected to my friends without keeping me in the app all the time. But social media can’t, and that’s why Instagram competes with TikTok which competes with Netflix which competes with Fortnite.

Mosseri touches on another idea that has a lot of currency these days: people prefer to socialize in DMs.

Journalist Taylor Lorenz has written about this a number of times, most recently in a newsletter entitled You Don’t Want The Old Instagram.

She writes:

It’s tempting to think that if Instagram simply reverted to a previous design or reinstated a chronological feed, that would somehow bring us closer to the people we care about. But we don’t forge personal connections by sharing or commenting on highly personal public-facing photos that are permanently displayed on a grid anymore. These days, intimacy is fostered through features like DMs, group chats, or ephemeral posts to Close Friends.

I think this is correct, but it’s missing something important: Instagram was always an inferior way to connect with people. In fact, a number of Taylor Lorenz stories are about teens coming up with clever substitutes for things that used to be very easy on Facebook. In “Re-creating Facebook”, Lorenz writes about how incoming college freshmen for the class of 2023 made “class page” Instagram accounts where they could introduce themselves to each other—an objectively worse experience than using a native platform feature for groups. A Huntington Beach teenager tried to use TikTok to tell kids at his high school about his party and accidentally started a riot instead. Lorenz is right that I don’t want the old Instagram. I want the old Facebook.

Doing everything social in group chats or ephemeral stories is a full retreat from the utopian promise of the internet. It surrenders the possibility that you could ever form new connections online as yourself. The internet has proven to be such an inhospitable environment for living your full life that we mostly socialize privately or on platforms like Discord or Reddit, where anonymity is the default. I don’t deny that these are rational responses to the social, cultural, and political landscape we live in—I haven’t tweeted under my own name in years!—I just think it sucks.

After years of the Facebook friend request, or the Instagram follow request, we’re back to a place where the most reliable way to stay in touch with someone you met in real life is to ask for their telephone number, a 20th century technology that is only halfway reliable as an identifying piece of information because the 1996 Telecom Act requires that carriers allow you to transfer your number. That is not progress.

I hear what a geezer I sound like. Sure, maybe I think that a Facebook group is somehow still the ideal way to organize an adult softball team, but I’m also the kind of person who needs to find an adult softball team. I know that the next generation is going to innovate in how they connect with each other and that in hindsight those innovations will seem as natural to them as the digital photo album seemed to me. I love them—and I’m proud of them.

But I’m sorry that this is the internet we’ve left them. We no longer suffer the naiveté that just putting people in one giant digital room will lead to some inherent understanding about our fellow man. But we also lost something extremely practical: a network specifically designed for augmenting our in-person relationships, not replacing them. When your digital life manifests in the physical world today, more often than not, it’s because something went horribly wrong.

At the very least, it used to be a lot easier to plan a party.

Thanks to Parker Richards for his feedback on a draft of this post.